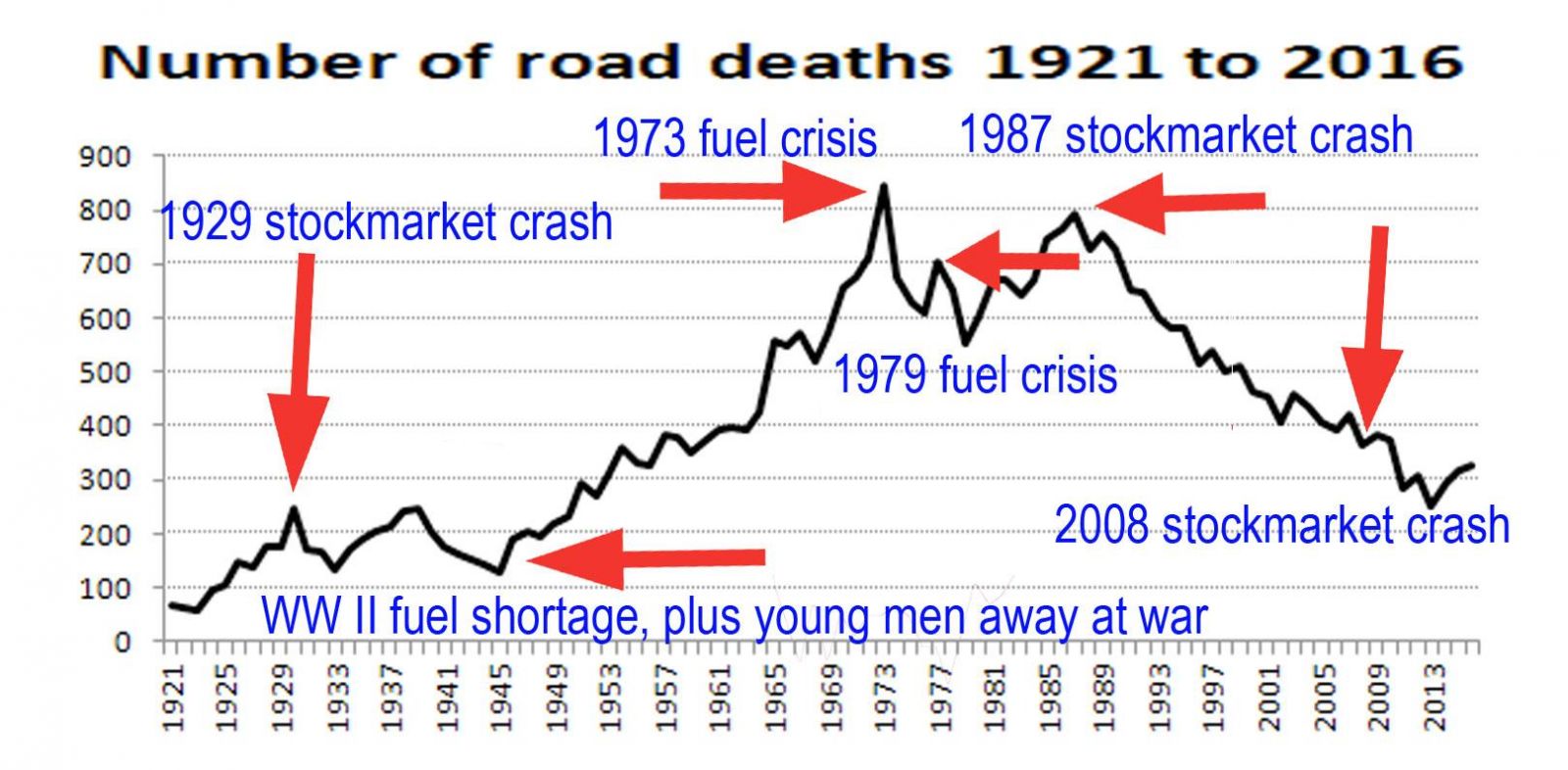

A simple graph, published by the car review website dogandlemon.com, shows how New Zealand’s road toll has consistently followed the ups and downs of the economy.

Editor Clive Matthew-Wilson, who is an outspoken road safety campaigner, says:

“The road toll grew for the first 87 years of the twentieth century, because the authorities tried to reduce accidents by changing driver behaviour. This was a complete failure."

"The road toll began its long fall in the late 1980s when the authorities began focusing on changing the roads and cars instead. Median barriers began preventing head-on collisions on some of the nation’s most dangerous roads. Second-hand Japanese cars modernised the vehicle fleet. Emergency medical teams were given helicopters; cellphones gave ordinary people instant access to emergency services. Attitudes to health and safety improved, along with increased enforcement by police. Those are the main reasons for the lowering road toll, which is now half of what it was in the 1970s.”

“However, although the overall road toll has been dropping since the 1980s, the peaks and falls have always closely followed the economic conditions.”

Globally, trends in road fatalities are similar. In New Zealand there was a 37% decrease in fatalities between 2000 and 2014, and a 42% decrease in fatalities in the 32 OECD countries over the same period.

However, New Zealand and 19 other OECD countries experienced a recent increase in fatalities. For example, 2015 saw a 15.4 percent increase in Israel compared to 2014; Finland,13.5 percent and Austria 10.5 percent.

Between 2015 and 2016, Australia also experienced an increase of 7.9 percent.

Matthew-Wilson says the five big factors driven by the economy are motorbikes, trucks, car numbers, fuel prices and unemployment.

“Poor people die more often on the roads than rich people. The groups most likely to be unemployed during recessions, such as builders’ labourers, get jobs again as the economy recovers. Because builders’ labourers tend to be heavy drinkers with a casual attitude towards health and safety, and because they tend to drive older vehicles, this group causes a disproportionate percentage of road deaths. Sciencedaily.com estimates that each one-percentage point decrease in the overall unemployment rate is associated with a 9-percent increase in national fatalities.” (other studies have shown less dramatic estimates, but all agree that unemployment is linked to a lower road toll).

"However, it’s not just builders’ labourers raising the road toll. As economies grow, so do the numbers of trucks moving goods."

“Trucks themselves are a major, growing road safety hazard. In 1980, accidents involving trucks made up 12% of the road toll. In 2016, accidents involving trucks made up 23% of the road toll. That’s one of the major reasons our road toll is going up and not down.”

“And, as the economy recovered from the 2008 crash, more middle-aged men had money to spare. They bought motorbikes, and are killing themselves in record numbers.

"Globally, the road toll tends to rise and fall with the number of motorcyclists. This is reflected in the 2018 New Zealand road toll: there were 13 serious crashes involving motorbikes in the first three weeks of January alone.”

“Motorbike crashes are now a huge percentage of the road toll.”

Matthew-Wilson says a rise in the number of vehicles has also driven the road toll higher.

“The numbers of cars on the road has climbed dramatically. The more vehicles, the more crashes. It's that simple.”

“Fuel prices also dropped in the period after 2014. The cheaper the fuel, the more trips. The more trips, the more crashes."

Matthew-Wilson says the key to lowering the road toll is simple:

“Improve the roads, improve the cars, make it harder to get a motorbike licence and re-target enforcement to high risk groups, such as drivers using cellphones and not wearing seatbelts.”

“Just before the road toll started falling in the late 1980s, the Auckland harbour bridge used to suffer one serious accident a week."

"Multiple attempts were made to improve the standard of driving on the harbour bridge, and they all failed. Eventually the authorities built a concrete barrier between the opposing lanes of traffic, and the serious accidents virtually stopped overnight. There wasn’t one less idiot on the road, but the road had been changed in a way that prevented simple mistakes becoming fatalities.”