Economic recession kept the 2025 road toll low, says the car review website dogandlemon.com.

As at 5pm on December 31, 2025, the New Zealand road toll was 270, compared to 292 for the whole of 2024.

.jpg)

Editor Clive Matthew-Wilson, who is an outspoken road safety campaigner, says:

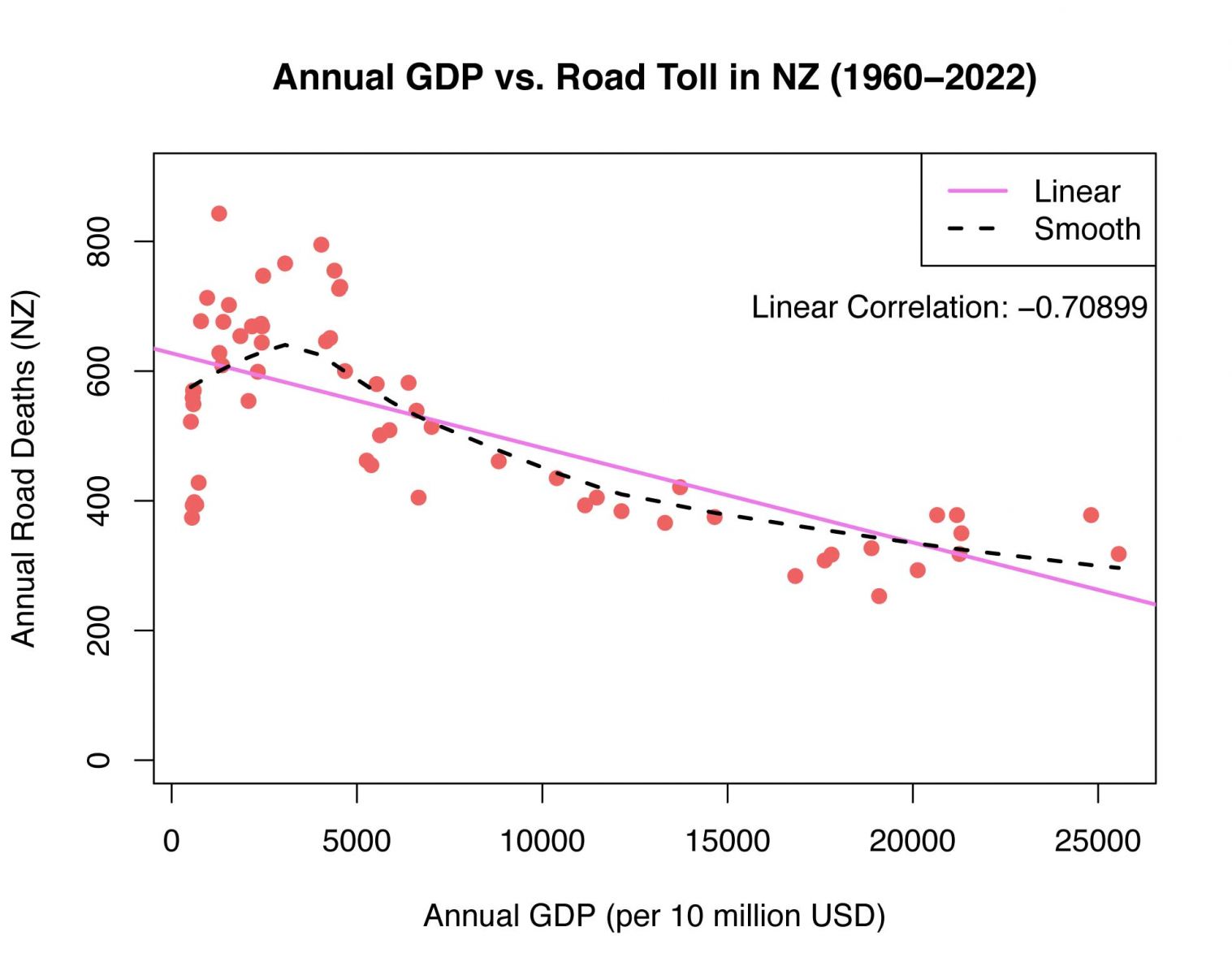

“There is broad international consensus — among organisations as diverse as the World Health Organisation, the OECD, the World Bank, together with the vast majority of major road safety researchers — that economic conditions and road deaths are closely linked."

“The International Transport Forum at the OECD, an intergovernmental organisation with 69 member countries (including New Zealand), states bluntly:

"There is clear evidence that when economic growth declines and particularly when unemployment increases, road safety improves."

Matthew-Wilson adds:

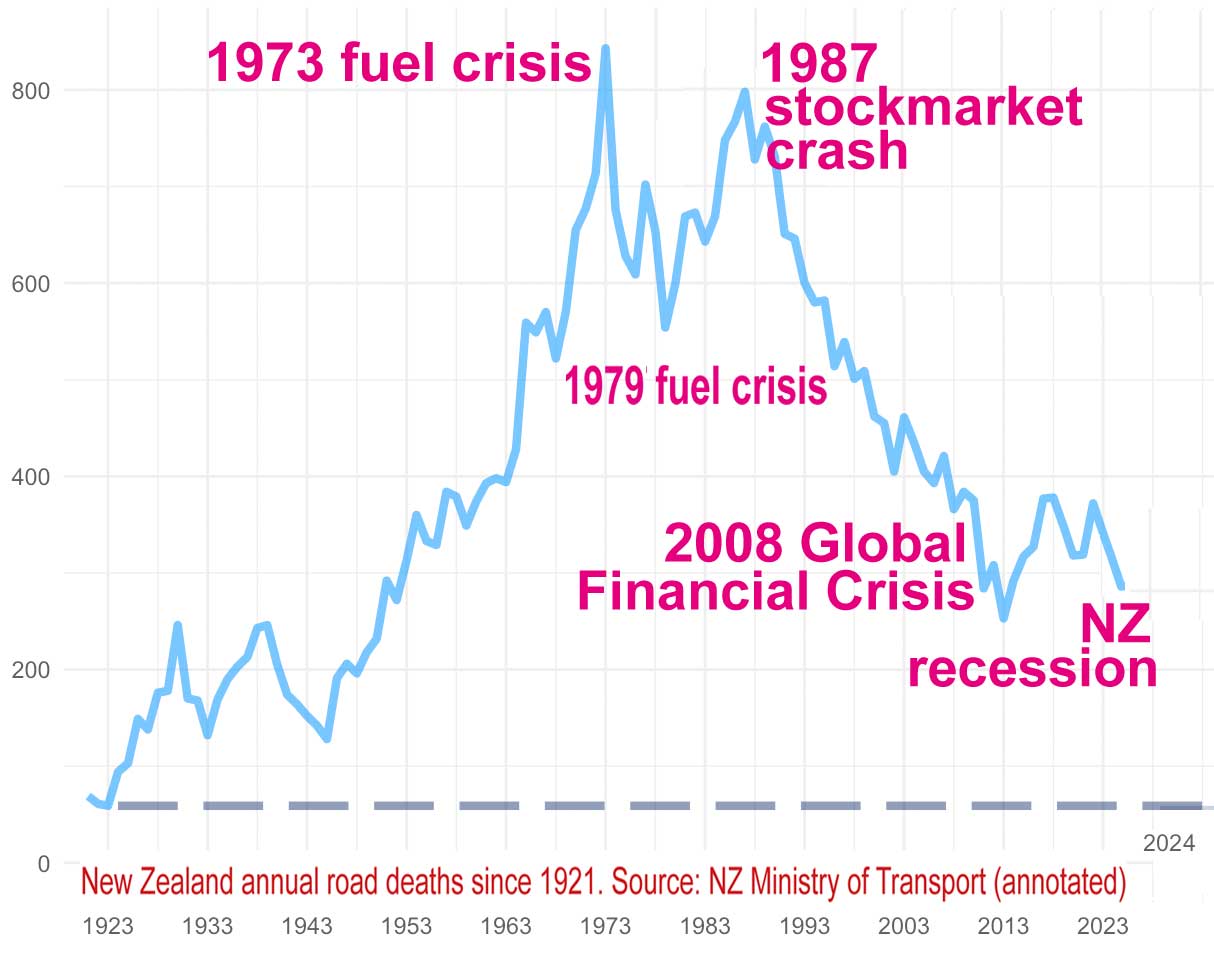

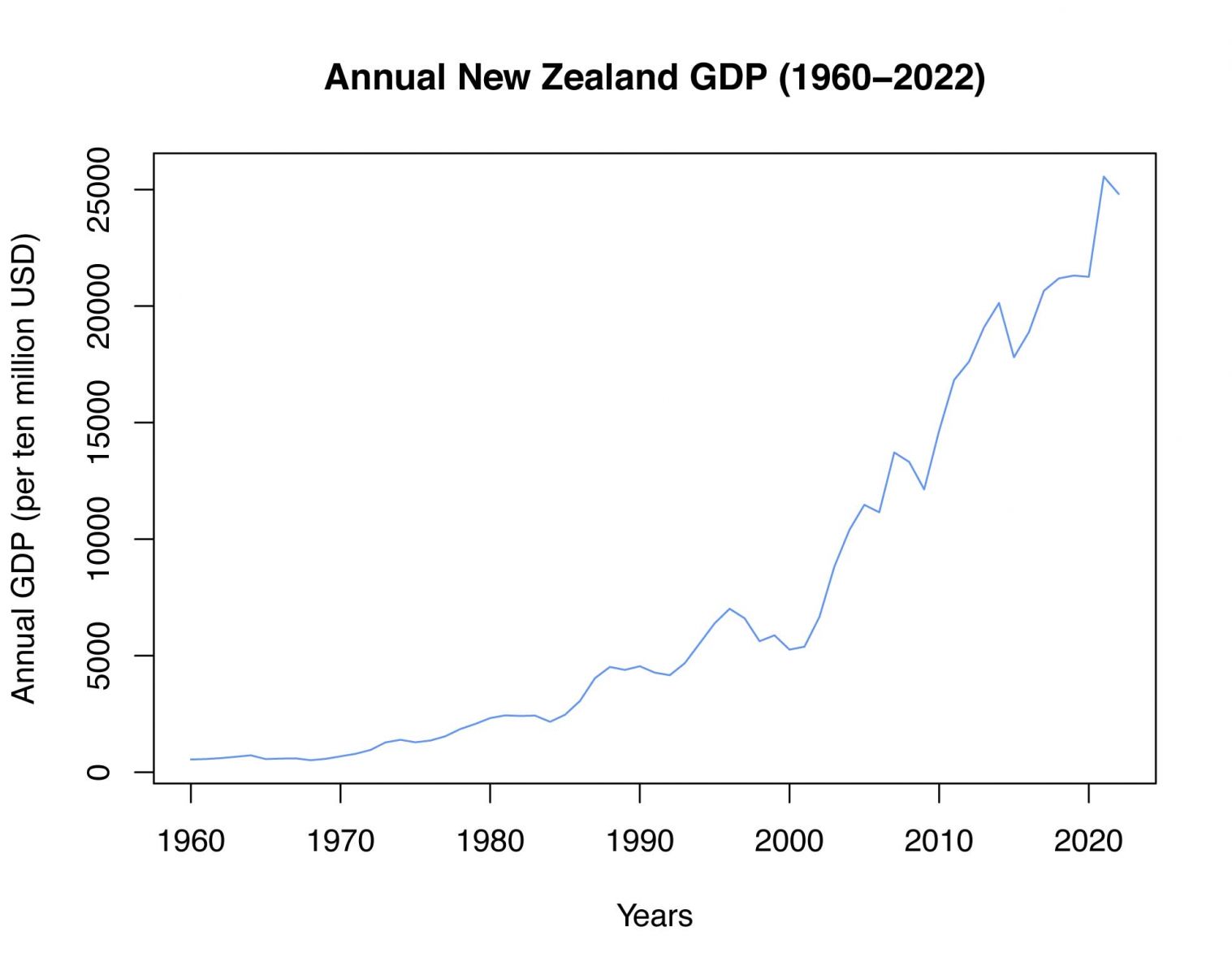

“The overall road toll in New Zealand has been steadily falling since the late 1980s, but the annual highs and lows of the toll closely follow the highs and lows of the economy.”

"unemployment is a good predictor of the road toll: high unemployment means a lower road toll, and vice versa".

New Zealand’s worst road toll was 1973, when 843 people died.

Matthew-Wilson says the reasons for the high 1973 road toll are painfully obvious:

“There was very low unemployment in the early 1970s and fuel was cheap. So was alcohol. Driving after drinking was normal. Most of the affordable cars were decades old, had terrible tyres and often lacked seatbelts. Seatbelt use was optional before 1972. Those who couldn’t afford a car often rode motorbikes, but helmets were not compulsory at all speeds until 1973. Prior to 1973, helmet use was only required for riders exceeding 50kp/h. The 80km/h speed limit (which was already widely ignored) was raised to 100km/h in 1969. The result was carnage."

"Then the 1973 fuel crisis crashed the world’s economy."

"One year later, the road toll had dropped by nearly 200, to 676.”[1]

“The second highest road toll (797), was in 1987, just before the global sharemarket crash. The next year the toll had dropped by another 70, to 727.[2]”

“After 1987, the road toll continued its fall, to this day, due to four main factors: the improvement of the vehicle fleet that began with the mass importation of safer used Japanese cars[3], the gradual installation of median barriers and other highway improvements, the growing enforcement of speed, drink-driving and seatbelt laws and the vastly improved medical trauma response system. A possible fifth factor was the gradual mass adoption of cellphones, which enabled motorists to contact emergency services from a significant proportion of the country. However, cellphones have also increased the risk of accidents caused by distraction."

Road deaths are not democratic

Poor people die more often on the roads than rich people.

“Poverty, in terms of lack of education, substance abuse and poor quality vehicles, appears to heavily influence the road toll. The same drivers most likely to crash are also most likely to be impaired and are often not wearing a seatbelt at the time of the accident.”

About two-thirds of fatal accidents occur on rural roads, many of them far beyond the reach of speed cameras and police radar. A large percentage of these deaths are males, with Maori heavily over-represented.

“A significant percentage of industrial workers are heavy drinkers with a casual attitude towards health and safety. Worse, 3/4 of New Zealand drivers who die in drug-related crashes have more than one substance in their system. According to Waka Kotahi, the combination of alcohol, illegal drugs and legal medication can increase your risk of an impaired fatal crash by 23 times.”

"The groups most likely to be unemployed during recessions, such as mill workers, often get jobs again as the economy recovers, so the road toll will go up again once the factories start hiring once more.”

The mortality rate for males is consistently higher than the rate for females. In 2019, the mortality rate for males was 9.5 deaths per 100,000, compared to 3.6 per 100,000 for females.

Younger adults (15–24 years) and older adults (75+ years) have higher mortality rates in vehicles. Unfortunately, older people are more fragile. Mortality rates among pedestrians were also highest in older adults.

The highest mortality rates were for males 85 years and over.

Motorbikes are the highest risk group

In 2024, there were 52 fatal crashes, 547 serious injury crashes, and 806 minor injury crashes involving motorcyclists. So about one in five fatalities involved motorbikes.[4]

Matthew-Wilson points out:

“In the last two decades there has a been a huge spike in the number of deaths of middle-aged men riding large motorbikes. These motorcyclists were at more than 100-times greater risk of death than non-motorcyclists.”

“While sales of these large bikes tend to drop during recessions, the men who already own them are likely to keep riding, although they may ride less often. So, motorbike accidents are likely to eventually fall also, but perhaps not as fast as car and truck accidents.”

Trucks are involved in about 18% of fatal road crashes

“Recessions mean fewer trucks on our roads. As economic activity increases at the end of a recession, so do the numbers of trucks moving goods. Therefore, the road toll rises once more."

“Trucks are a major road safety hazard: in 1980, accidents involving trucks made up 12% of the road toll. In New Zealand, trucks typically account for around 18% of fatal crashes and 10-20% of all road deaths, though this varies annually. In 2024, trucks were involved in just 16.1% of fatal crashes. That’s far lower than in recent years, probably due to economic recession, which almost always reduces the number of truck movements.”

Twice recently, trucks drivers caused serious fatal accidents while using cellphones. In December, Robert Wayne Clifford was jailed after admitting using his phone as his truck smashed into a van, killing one person and injuring five others.

Clifford had been caught using a cellphone while driving four times before.

Sarah Hope Schmidt was last year sentenced to two years and four months in prison after crashing her 30-tonne truck and trailer unit into the back of stationary vehicles, killing another driver.

During her nearly-two-hour trip before the accident, Schmidt had been using her handheld phone for 44 minutes, or 38% of the entire journey. Schmidt looked up just two seconds before the crash on the Hawke’s Bay Expressway which killed 22-year-old Caleb Baker.

Matthew-Wilson believes drivers who use cellphones in moving vehicle should have their phones confiscated. Repeat offenders should have their vehicle confiscated.

Trucks are also implicated in a large percentage of cyclist deaths.

The Greens want to save lives by eliminating private cars

“The Greens are acutely aware that rising global temperatures risk extinguishing human life on Earth. The private car is a potent symbol of climate change, so the private car has become a primary target of Greens across the globe.

Therefore, the Greens believe the best way of saving lives is to eliminate private cars, especially cars powered by fossil fuels.[5]

However, Matthew-Wilson points out that “most of New Zealand lacks public transport, especially at night, and most rural dwellers would be completely stranded without a car. Greens tend to live in safe, comfortable urban neighbourhoods where cycling can be fun. Urban Greens often have little idea of how big an issue transport is in rural areas.”

Matthew-Wilson supports the idea of electric cars, but believes the ongoing bankruptcies plaguing the electric car industry make an electric car purchase risky for those on a budget.

“If the government wants to hand out free electric cars to motorists, go ahead; but remember, when ordinary people are buying their own transport, affordability and reliability are top priorities. Most electric cars can’t answer these needs at present. There are some affordable and reliable electric vehicles, such as the Nissan Leaf, but these vehicles are mostly old and have a limited range that would not suit many rural motorists."

Speed limits are political football

Matthew-Wilson believes it’s important not to let political ideologies dominate road safety strategies.

“Speed is never good nor bad, it is merely appropriate to the conditions. For example, the fastest legal road in the country – the Waikato Expressway – is also one of the safest roads in the country.

"On the other hand, there is clear evidence that higher urban road speeds are associated with increased deaths and injuries, especially to pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists."

However, Matthew-Wilson points out that many arguments against speed are actually arguments against cars generally.

“All the arguments against a speed limit of 110km/h, apply equally to a speed limit of 100, 90 ,80, 70, 60, 50, 40, 30, and so on, down to zero. The debate about speed is really a debate about the role that cars play in a warming world.”

In December of 2019, the Labour/Greens government announced a policy of lowered speed limits on numerous state highways and local roads across the country, as part of its 'Road to Zero' road safety strategy. ‘Road to Zero’ consistently failed to meet its targets.

In 2025, the National/Act government raised many of these speed limits again. Despite claims that the raised speed limits would mean a bloodbath on our roads, in fact, there has been no clear national spike in road deaths tied directly to recent speed limit increases. The overall road toll did not rise significantly from the previous year. Road deaths during many holiday periods in 2025 were significantly lower than the previous year.

“The same people who predicted carnage once the speed limits were raised again are the same ones who predicted carnage when the speed limits were previously raised on the Waikato Expressway."

"However, the government can take no credit for this relatively low road toll, except that its economic policies induced the economic recession."

“I’m not saying the current government was correct to raise the speed limits on many roads. I’m saying that the original speed restrictions were based on ideological goals, with road safety used as an excuse[6]. This arbitrary drop in speed limits alienated rural motorists and contributed to a change of government. Arguably, the Greens’ speed limit policy was irresponsible, because it led to the election of their ideological enemies.”

“The current government also raised speed limits for ideological reasons, which was equally irresponsible. Worse, the current government appears to be fixated on grand highway schemes, instead of simple modifications that would make our everyday roads far safer.”

The Waikato Expressway example shows it’s simply wrong to claim that higher speeds automatically lead to more road deaths. However, it’s completely correct to say that inappropriate speeds are likely to lead to more road deaths. Therefore, speed limits must be based on science, not ideology.”

The speed of the average driver is not the major issue

In 2009, the New Zealand Automobile Association “examined over 300 fatal crash reports from 2008, to see which patterns emerged.”

The AA concluded that “[It’s not] true that middle-New Zealand drivers creeping a few kilometres over the limit on long empty straights dominate the road toll... Only one in six fatal crashes were reported over the speed limit – and they were well over... [These fatal accidents] were caused by people who don’t care about any kind of rules. These are men who speed, drink, don’t wear safety belts, have no valid licence or WoF – who are basically renegades. They usually end up wrapped around a tree, but they can also overtake across a yellow line and take out other motorists as well.”

Matthew-Wilson agrees, adding:

“Speed is never good nor bad, it is merely appropriate to the conditions. Let me repeat: the fastest legal road in the country – the Waikato Expressway - is one of the safest roads in the country."

“According to the Ministry of Transport, speed-only is the primary cause of just 11% of fatalities. A very large percentage of these speed-related fatalities involve poorly-educated young males or reckless motorcyclists. A far larger percentage of speed-related accidents also involve substance abuse. Substance abuse prompts drivers to speed in ways that often kill.”

“These high-risk groups typically ignore speed signs, speed cameras and road safety messages. Threatening to take their driver’s licence generally doesn’t work, partly because the high risk groups often don’t have a driver’s licence.”

Matthew-Wilson gave the example of 19-year-old Piata Amelia-Blaise Otufangavalu, who killed five people (including herself) in a head-on crash on State Highway 3 in May 2024.

Coroner Matthew Bates said not only had Otufangavalu been huffing nitrous oxide, but there was cannabis in her system, which potentially exacerbated her impairment.

Otufangavalu never had a driver’s licence.

Matthew-Wilson asks:

“How would a lowered highway speed limit have prevented this tragedy? Heavier enforcement might have spotted this driver’s behaviour earlier, but long experience has shown that chasing young offenders frequently ends in further road deaths."

“But median barriers would have prevented this head-on collision.”

“Fines work as a deterrent for middle-class people with accessible incomes. However, fines are often largely ineffective against the people most likely to cause fatalities.”

Matthew-Wilson’s conclusions are backed up by the largest study of fines as a deterrent ever conducted in Australia, which concluded that fines and disqualification do not reduce the risk of offending.

“And, sadly, asking people to drive safely is an expensive waste of time.”

“Even more depressing are the constant calls to repeat failed road safety initiatives, such as advanced driver/rider training”.

See also our explanation: "why the term ‘average speeds’ can be misleading" under [1] below.

Keeping it simple

Matthew-Wilson says the key to lowering the road toll is simple:

“Improve the roads, improve the cars, move longhaul road freight from trucks to rail, make it harder to get a motorbike licence and re-target enforcement to high-risk groups, such as impaired and reckless drivers, drivers using cellphones and vehicle occupants who are not wearing seatbelts.”

“Just before the road toll started falling in the late 1980s, the Auckland harbour bridge used to often suffer one serious accident a week[7].”

“Multiple attempts were made to improve the standard of driving on the harbour bridge, and they all failed. Eventually the authorities built a concrete median barrier between the opposing lanes of traffic, and the serious accidents virtually stopped overnight. There wasn’t one less idiot on the road, but the road was changed in a way that prevented simple mistakes from becoming fatalities.”

It has been claimed that the dramatic drop in the road toll was the result of the lowering of the official speed limit from 100km/h to 80km/h in 1973. However, Clive Matthew-Wilson (who was learning to drive at the time) dismisses this claim as “mostly wishful thinking."

"A 1982 government study* concluded the attempts at speed enforcement had been largely ineffective, stating there was: “[no] discernible link between rural speed limit [enforcement] and [the] speeds [drivers had actually travelled at] since 1974”.

"Multiple studies have shown that higher fuel prices tend to reduce the road toll, because people drive less and change their driving habits, thereby reducing the risk of accidents."

[2] The same thing occurred after the the 2008 Global Financial Crisis: In 2007, the road toll was 421. After the 2008 crash, the road toll dropped to 366, and, after a couple of slight rises, continued to fall until 2013, when the road toll was just 253. The two graphs above show the same clear trend.

[3] Iain McGlinchy, who spent 17 years as a policy advisor at the New Zealand Ministry of Transport, says the introduction of used imports was one of the best things that happened to the NZ vehicle fleet.

“We got much newer and safer vehicles,” he says. “Until about 2005, the [used Japanese imports] were better on every level than [most cars sold new in New Zealand], because we were able to cherry-pick the top-spec models from Japan.”

[4 ] Motorcycles tend to have high crash rates in part because they tend to attract risk-taking riders, such as young adult males, who also tend to have equally high crash rates when driving cars. Similarly, young men tend to bicycle more than average, which may contribute to higher crash rates among cyclists. As a result, a cautious adult cyclist with a reliable bike and safety equipment (such as helmets and lights) who observes traffic rules, may have significantly lower crash risk than average bicyclists who are more likely to ride in a risky manner.

[5] The Greens are hoping that if New Zealanders reduce their emissions, then the major nations driving climate change, such as China, the United States, India, and the European Union, will do the same.

The idea that New Zealand's actions inspire larger nations is optimistic; realism suggests major emitters (US, China, India, EU) act primarily due to their own economic and political self-interest. However, the Greens argue that NZ's leadership may influence international attitudes and set precedents, while also offering economic benefits like energy security and innovation for NZ itself.

[6] This is not the first time the Greens have allowed ideology to override common sense. The previous Labour/Greens government made it far harder to pass the WOF safety check. The idea was that, by making it harder for motorists to drive older cars, these motorists would be motivated to buy new or newer cars, which would reduce emissions. Sadly, the actual outcome was that making Warrants of Fitness harder to pass simply increased the number of vehicles driving illegally.

[7] “The latter half of 1989 was a particularly bad period for road accidents on the bridge. There were nine fatalities between July 1989 and February 1990. A Japanese tourist was killed when her motorcycle hit a small ridge between lanes and she was catapulted into the path of an oncoming truck. A trailer broke free from a utility and smashed into the following car, killing the woman driver. Worse still, on the evening of 24 November 1989, a wildly out-of-control northbound car spun across three lanes at high speed and collided with a southbound car that had not the slightest chance of avoiding it. Just three days later, a Dunedin doctor was killed when his car skidded across six lanes and hit a vehicle on the very outside lane.”