A weaker economy almost always means a lower road toll, says the car review website dogandlemon.com.

Editor Clive Matthew-Wilson, who is an outspoken road safety campaigner, was commenting after a record low road toll during the recent Labour Weekend holiday period.

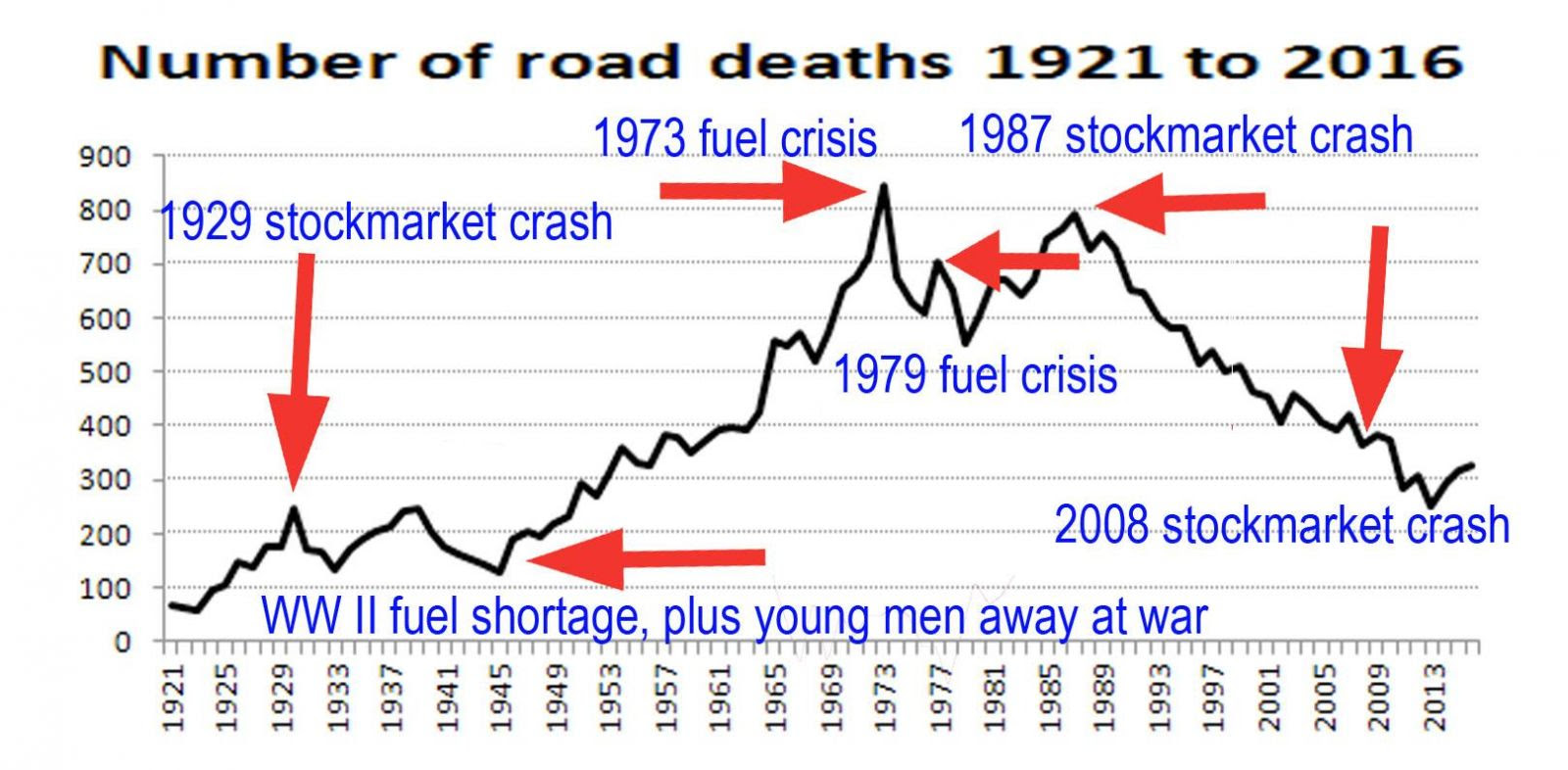

“First, the Labour Weekend weather was crap, so many families stayed home. Second, New Zealand’s recent poor economic performance means a corresponding drop in the road toll. A similar phenomenon occurred in 2013, when the Labour Weekend death toll was one: the world’s economy crashed in 2008 and the road toll crashed with it. Both the global economy and the road toll took several years to recover.”

“Poor people die more often on the roads than rich people. The groups most likely to be unemployed during recessions, such as builders’ labourers, get jobs again as the economy recovers. Because builders’ labourers tend to be heavy drinkers with a casual attitude towards health and safety, and because they tend to drive older vehicles, this group causes a disproportionate percentage of road deaths.”

Sciencedaily.com estimates that each one-percentage point decrease in the overall unemployment rate is associated with a 9-percent increase in national fatalities.”

“Currently, unemployment among the young is high, which is undoubtedly bad for them but probably good for the road toll.”

"However, it’s not just builders’ labourers raising the road toll. As economies grow, so do the numbers of trucks moving goods.”

“Trucks themselves are a major road safety hazard. In 1980, accidents involving trucks made up 12% of the road toll. In 2022, accidents involving trucks made up 19% of the road toll. That’s one of the major reasons our road toll is as high as it is.”

Matthew-Wilson says speed has become a political football: “The squabbling between the Greens and the rednecks over speed really doesn’t help."

“Speed is never good nor bad, it is merely appropriate to the conditions. The fastest legal road in the country – the Waikato Expressway – is also one of the safest."

“On the other hand, when cars, bikes and pedestrians are moving in close proximity, much lower speed limits are appropriate. However, in practice, it’s often far safer to physically protect vulnerable road users, using roadside fencing and raised pedestrian crossings.”

Matthew-Wilson believes lowered speed limits often make little or no difference to high-risk offenders.

“About two-thirds of fatal accidents occur on rural roads, many of them far beyond the reach of speed cameras and police radar. A large percentage of these deaths are males, with Maori heavily overrepresented. Poverty, both in terms of lack of education and poor quality vehicles, appears to heavily influence this road toll. The same drivers most likely to crash are also most likely to be impaired and are often not wearing a seatbelt at the time of the accident.”

Matthew-Wilson is also concerned at the number of motorbike accidents.

• "Globally, the road toll also tends to rise and fall with the number of motorcyclists. This is reflected in the New Zealand road toll:

• “In the last two decades there has a been a huge spike in the number of deaths of middle-aged men riding large motorbikes. These motorcyclists were at more than 100-times greater risk of death (respectively) than non-motorcyclists.”

• “While sales of these large bikes tend to drop during recessions, the men who already own them are likely to keep riding, although they may ride less often. So, motorbike accidents are likely to eventually fall also, but perhaps not as fast as car and truck accidents.”

Matthew-Wilson says the key to lowering the road toll is simple:

“Improve the roads, move longhaul road freight from trucks to rail, improve the cars, make it harder to get a motorbike licence and re-target enforcement to high risk groups, such as impaired, reckless, drivers, drivers using cellphones and vehicle occupants who are not wearing seatbelts.”

“Just before the road toll started falling in the late 1980s, the Auckland harbour bridge used to suffer one serious accident a week."

"Multiple attempts were made to improve the standard of driving on the harbour bridge, and they all failed. Eventually the authorities built a concrete barrier between the opposing lanes of traffic, and the serious accidents virtually stopped overnight. There wasn’t one less idiot on the road, but the road had been changed in a way that prevented simple mistakes from becoming fatalities.”